Mel Hulse was always armed...with a long list of roses needed for the San Jose Heritage Rose Garden. There was nothing typical about Mel's lists. They were prodigious in scope and quantity: 300 pieces of budwood to be de-eyed in a morning; 35 miniature rose standards budded by Burling Leong to be transported from Ralph Moore's Sequoia Nursery to San Jose; and, on a rose rustle, 56 found roses to be re-collected, propagated, grown out and replanted in the Heritage.

One fall, the Gold Coast Heritage Roses Group gathered in Nevada City at the north end of the Highway 49 corridor. Early in the morning, we rendezvoused in a small town about 35 minutes north. Teams of rosarians fanned out to survey roses about town. A small field had large plants in a grid about 10 feet apart, obviously rootstock. An enormous, smooth rambler sat by the road about 30 feet from the Autumn Damask. Two small cemeteries were situated at opposite ends of town. Detecting roses there was not easy. The cemeteries were heavily wooded but otherwise stripped of foliage. Hawk-eyed Jeri Jennings knew where to look, and cuttings of a small, struggling China were collected.

Mel and Jill Perry, the curator of the Heritage, led the caravan to a state park further north, a manmade badlands from placer mining that washed away hillsides in the search for gold. Roses were even harder to find, as the state parks were skilled at removing undergrowth and reducing the landscape to a grassy park maintainable by herbicide and weed trimmers. After checking a small cemetery and an old ghost town, we sadly concluded the rose we came to collect was nowhere to be found.

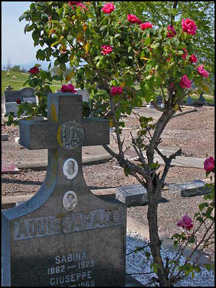

We saddled up and headed down California's scenic Highway 49 to Placerville. The landscape was different, milder, drier, another microclimate. Up early the next day, we convened at a large civil war cemetery on the edge of town. This cemetery was still in care, the roses in much better shape. A large noisette graced one headstone, a lovely Pernetiana another, a decent sized 'Archduke Charles' another. As always, Mel paused to remember the departed, reading the headstones of families that lost two, three or four children, probably to the ravages of epidemics. We studied the language of monuments, the finger pointing toward heaven, the broken log representing those cut down in their prime, lambs on the headstones of children.

We almost had our own brush with the law. Someone called the cemetery board to ask if the gate could be unlocked for those of our group unable to hike a deer trail into the cemetery. Instead, we were threatened with arrest if we weren't out by noon. The image was almost comic - - the curators of two historic rose gardens, members of the Gold Coast Heritage Roses Group, two hobbling with canes, two reporters from The Sacramento Bee, and two members of the Sacramento Old City Cemetery board - - arrested for trespass in a cemetery. We moved on.

Further down Highway 49, we stopped at a beautiful old cemetery shaded by tall trees, truly a gem. Old roses were plentiful, sometimes two or more to a gravesite. This cemetery had happily escaped the attentions of the weed-trimmer-and-Roundup crew. An old Tea lives side by side with an old moss. And so it went, as we wove our way down Highway 49, visiting Gold Country cemeteries abandoned by time, a few strong roses among the headstones of pioneering families.

After 10 years of practice, Mel was a wizard at selecting softwood cuttings. He needed to be. The typical "found rose" in California, with its annual seven month drought, is not a pretty sight. Most of us collect cuttings to propagate by carefully studying a healthy, vital plant, and choosing the perfect wood for the job. But a found rose - browsed by deer, infested with rose curculio, parched by drought, crowded by weeds, trees and undergrowth, and abandoned by gardeners - a found rose often yields only a tiny handful of ratty, half-eaten sunburned twigs from the top of the plant. Carefully tagged and marked, these so-called cuttings filled coolers in the back of Mel's little red rocket.

At the last stop on the final day, Mel surveyed his carload of cuttings. Summoning the voice of command, he asked for volunteers. Most rose rustlers don't mention that each two or three-day road trip is followed by dozens of hours devoted to attending cuttings. I never said no to the Colonel. And more often than not, Mel's cuttings would strike.

Mel came to roses late in life, bringing his wide-ranging talents to the task at hand. One of his unsung skills was manpower. When there wasn't enough room to propagate cuttings, Mel trained more rosarians to propagate cuttings. When roses wouldn't grow on their own roots, Mel trained more rosarians to bud. When there weren't enough volunteers to prune the San Jose Heritage Rose Garden, Mel trained more gardeners to prune. And when unidentified, found roses needed to be replaced in public collections, Mel helped more rosarians rustle roses for public collections. Mel Hulse left us with his skills. The message to rosarians is irrefutable: if we want our passion for roses to survive the rigors of life in the 21st Century, we must actively share our passion, knowledge and skill with those who want to learn.

Thank you, Mel. We miss you.

Photos courtesy of the author